The Portrait

Hank O’Neal: Capturing Legends

Words: Lorraine Anne Davis

In 1981, I was living and working at Berenice Abbott’s “Blanchard Inn” on the Piscataquis River in Maine, where her darkroom, studio and offices were. Abbott lived a few miles away in a lakeside cabin she had built, leaving the three-story Blanchard home she had purchased with Elizabeth McCausland in the 1960s for guests and apprentices like me.

Jacqueline Onassis, New York City, December, 1979

In April of that year, when the snow was beginning to melt in earnest, Abbott’s good friend and biographer, Hank O’Neal, came to Maine with his then girlfriend to work with Berenice on a project. I was a lowly work-study student and had no idea who either of them were. When I asked his girlfriend what she did for a living, she told me she was a jazz singer. “You probably know my song ‘The Girl from Ipanema.’” I nearly fell over. The three of us spent the week running around at Berenice’s beck and call during the day, and in the evenings, chatting and playing Scrabble at the kitchen table.

Years later, I ran into Hank at a photography conference where he was giving a talk. A slender, towering New Yorker with an East Texas twang, O’Neal exudes southern charm and an indefatigable energy that he has channeled into his life’s pursuit of music, writing and photography.

O’Neal acquired his first camera at the age of 10, and at 13, got a job in a music store, where he spent his hard-earned cash on jazz records. Long steeped in jazz and photography, by the time he left his “day job” at the CIA in the 1970s, he had founded the jazz label Chiaroscuro Records. According to the company website, “There was no other U.S.-based record company at the time, large or small, that produced such a wide variety of music, ranging all the way from the Harlem stride style of Willie the Lion Smith to Bill Evans with The National Jazz Ensemble.” Chiaroscuro produced more than 100 records between 1970 and 1978.

Years later, I ran into Hank at a photography conference where he was giving a talk. A slender, towering New Yorker with an East Texas twang, O’Neal exudes southern charm and an indefatigable energy that he has channeled into his life’s pursuit of music, writing and photography.

O’Neal acquired his first camera at the age of 10, and at 13, got a job in a music store, where he spent his hard-earned cash on jazz records. Long steeped in jazz and photography, by the time he left his “day job” at the CIA in the 1970s, he had founded the jazz label Chiaroscuro Records. According to the company website, “There was no other U.S.-based record company at the time, large or small, that produced such a wide variety of music, ranging all the way from the Harlem stride style of Willie the Lion Smith to Bill Evans with The National Jazz Ensemble.” Chiaroscuro produced more than 100 records between 1970 and 1978.

Doc Cheatham at Home, New York City, September 18, 1986

Besides being a jazz connoisseur, record producer and music impresario, O’Neal photographed every day along the way, eventually publishing 23 limited-edition books and portfolios, and a stunning 19 books between 1973 and 2022. A 2023 Steidl book, titled You’ve Got to Do a Damn Sight Better than That, Buster —a memoir of his 19-year working friendship with Berenice Abbott—is slated to be released in May.

As a photographer, O’Neal switches easily between making portraits of Astrud Gilberto and Jackie Onassis with his 8×10 Deardorff against a cloud-painted studio wall at Downtown Sound, and at-home portraits of America’s jazz greats, while also working with the latter as record producer and concert/festival promoter. His non-portrait work produced several series such as End of the Line, in which he rode every New York subway station from end-to-end and photographed every end-station; and XCIA, a documentation of graffiti art across the five boroughs of New York.

A rare individual, O’Neal has lived multiple-layered lives simultaneously, and has touched countless artists along the way. In the music world he has known, befriended, recorded and photographed some of America’s best jazz musicians. He eventually joined the Board of the Jazz Foundation of America to help support these often-struggling and aging artists, providing them with much-needed medical care, finding them gigs and getting their rent paid.

As a photographer, O’Neal switches easily between making portraits of Astrud Gilberto and Jackie Onassis with his 8×10 Deardorff against a cloud-painted studio wall at Downtown Sound, and at-home portraits of America’s jazz greats, while also working with the latter as record producer and concert/festival promoter. His non-portrait work produced several series such as End of the Line, in which he rode every New York subway station from end-to-end and photographed every end-station; and XCIA, a documentation of graffiti art across the five boroughs of New York.

A rare individual, O’Neal has lived multiple-layered lives simultaneously, and has touched countless artists along the way. In the music world he has known, befriended, recorded and photographed some of America’s best jazz musicians. He eventually joined the Board of the Jazz Foundation of America to help support these often-struggling and aging artists, providing them with much-needed medical care, finding them gigs and getting their rent paid.

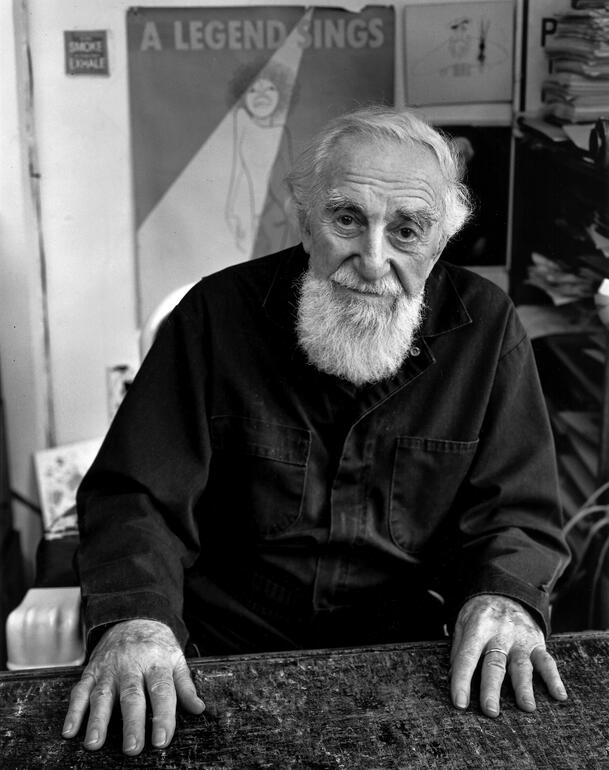

Al Hirschfeld in his Studio, New York City, January 23, 2002

The roster of greats he has known is beyond impressive, and with every song and every photograph there is a tale. O’Neal didn’t just record or photograph people, he knew them and their families, and was an important part of their lives, whether they were in the world of music or the world of photography. In 1973, he published his first book, The Eddie Condon Scrapbook of Jazz, and in 1976, A Vision Shared: A Portrait of America 1935-1943 was published. The Association of American publishers cited A Vision Shared as one of the 100 most important books of the decade. O’Neal, working directly with the FSA photographers he had befriended, created the book to reflect their words rather than the FSA for whom they’d been working. The book is the personal account by the photographers who documented America during the Great Depression. It was reissued by Steidl in 2018.

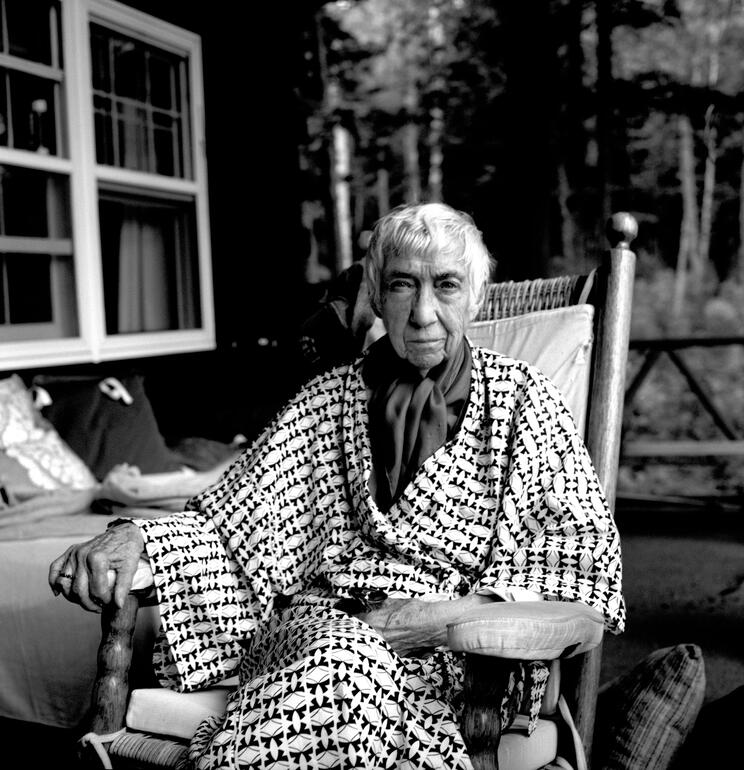

O’Neal’s long relationship with Berenice Abbott has also resulted in a number of books and projects. In the 1970s and 1980s, they traveled around Maine together photographing the state that she loved. One result of this collaboration resulted in a two-person exhibition of fifty-five prints that was her last photography project before she died.

His now-famous portrait of Jackie O came about when she was an editor at Doubleday. O’Neal relates: “Jackie—yes, I called her that—was the first editor on the book Berenice Abbott and I were doing together. She came down to my studio on a Sunday afternoon to discuss the book. After we’d sorted pictures for a couple of hours, she saw an old Atget book on a table. She was a big fan of Atget and asked if she could borrow it. I said, ‘Of course, if you’ll let me take a picture of you holding it.’

O’Neal’s long relationship with Berenice Abbott has also resulted in a number of books and projects. In the 1970s and 1980s, they traveled around Maine together photographing the state that she loved. One result of this collaboration resulted in a two-person exhibition of fifty-five prints that was her last photography project before she died.

His now-famous portrait of Jackie O came about when she was an editor at Doubleday. O’Neal relates: “Jackie—yes, I called her that—was the first editor on the book Berenice Abbott and I were doing together. She came down to my studio on a Sunday afternoon to discuss the book. After we’d sorted pictures for a couple of hours, she saw an old Atget book on a table. She was a big fan of Atget and asked if she could borrow it. I said, ‘Of course, if you’ll let me take a picture of you holding it.’

Berenice Abbott, Lake Hebron, Maine, July 17, 1991

“She thought that was a pretty good trade, so we headed downstairs to the studio room where the Deardorff was always set up underneath a large skylight. I only made three exposures; this was the second, about a second at f 8. She didn’t wiggle, and it came out okay. It is possibly the only posed large-format photograph of the most paparazzied woman of the 20th century that was made after the assassination of her husband. She returned the book a month or so later.”

Through Abbott, O’Neal met and befriended Lisette Model and dozens of other photography luminaries, including Brassai, Walker Evans, André Kertész, Robert Frank, Esther Bubley and iconic gallerist Lee Witkin, whose successor, Evelyne Daitz, gave O’Neal a retrospective in 1999.

It’s always a pleasure and an adventure to meet up with Hank in the Broadway loft where he has lived for the past 40-plus years. The ceilings are 18 feet high, and the walls are covered with framed photographs and bookshelves filled with CDs, LPs, cassettes and books. In the center is a grand piano, a few chairs and a worn leather sofa, where dozens of luminaries have sat and been photographed. Actors, writers, musicians, artists, publishers, recording executives, literary agents, ballet dancers, singers, poets and scribes have all passed through O’Neal’s loft. And, of course, he has a “New York Story” for each.

Through Abbott, O’Neal met and befriended Lisette Model and dozens of other photography luminaries, including Brassai, Walker Evans, André Kertész, Robert Frank, Esther Bubley and iconic gallerist Lee Witkin, whose successor, Evelyne Daitz, gave O’Neal a retrospective in 1999.

It’s always a pleasure and an adventure to meet up with Hank in the Broadway loft where he has lived for the past 40-plus years. The ceilings are 18 feet high, and the walls are covered with framed photographs and bookshelves filled with CDs, LPs, cassettes and books. In the center is a grand piano, a few chairs and a worn leather sofa, where dozens of luminaries have sat and been photographed. Actors, writers, musicians, artists, publishers, recording executives, literary agents, ballet dancers, singers, poets and scribes have all passed through O’Neal’s loft. And, of course, he has a “New York Story” for each.

Allen Ginsberg & William S. Burroughs, New York City, February 9, 1984

It was William Burroughs’ 70th birthday celebration when O’Neal photographed Allen Ginsberg and the Naked Lunch author sitting in front of the loft’s piano. The noted painter of the great depression, Raphael Soyer, was photographed in his New York studio when O’Neal was invited there by the filmmaker Erwin Leiser, where he was preparing to make a film about Soyer and Isaac Singer. The film was never made, but portraits of both men were. O’Neal and Soyer, also a friend of Abbott’s, maintained a relationship until Soyer’s death in 1987.

The portrait of Al Hirschfeld was taken a year before Hirschfeld’s death in 2003. O’Neal visited him at his home studio and photographed him behind his drawing table, where decades of Hirschfeld drawings were created. (The table now lives at the New York Public Library.) O’Neal took a number of 4×5s in both color and black and white, with Hirschfeld’s “magic hands” that have entertained millions splayed before him, and the “A Legend Sings” poster behind him, which O’Neal felt was appropriate. “Hirschfeld was a ‘jazzer,’ and a lovely, gracious man, who, by the way, drove his car around Manhattan until shortly before his death at 99 years, which is also legendary, if not surreal.”

O’Neal hopes to make a portrait book of all the legendary New Yorkers he has photographed, like Robert Frank and June Leaf, who he found sitting outside their Bleecker Street home in 2016 getting some sun. Frank grumbled to O’Neal, “Hank, why are you carrying such a big camera? It’s too damn big.” O’Neal photographed them, then immediately bought a smaller camera, which he uses to this day.

The portrait of Al Hirschfeld was taken a year before Hirschfeld’s death in 2003. O’Neal visited him at his home studio and photographed him behind his drawing table, where decades of Hirschfeld drawings were created. (The table now lives at the New York Public Library.) O’Neal took a number of 4×5s in both color and black and white, with Hirschfeld’s “magic hands” that have entertained millions splayed before him, and the “A Legend Sings” poster behind him, which O’Neal felt was appropriate. “Hirschfeld was a ‘jazzer,’ and a lovely, gracious man, who, by the way, drove his car around Manhattan until shortly before his death at 99 years, which is also legendary, if not surreal.”

O’Neal hopes to make a portrait book of all the legendary New Yorkers he has photographed, like Robert Frank and June Leaf, who he found sitting outside their Bleecker Street home in 2016 getting some sun. Frank grumbled to O’Neal, “Hank, why are you carrying such a big camera? It’s too damn big.” O’Neal photographed them, then immediately bought a smaller camera, which he uses to this day.

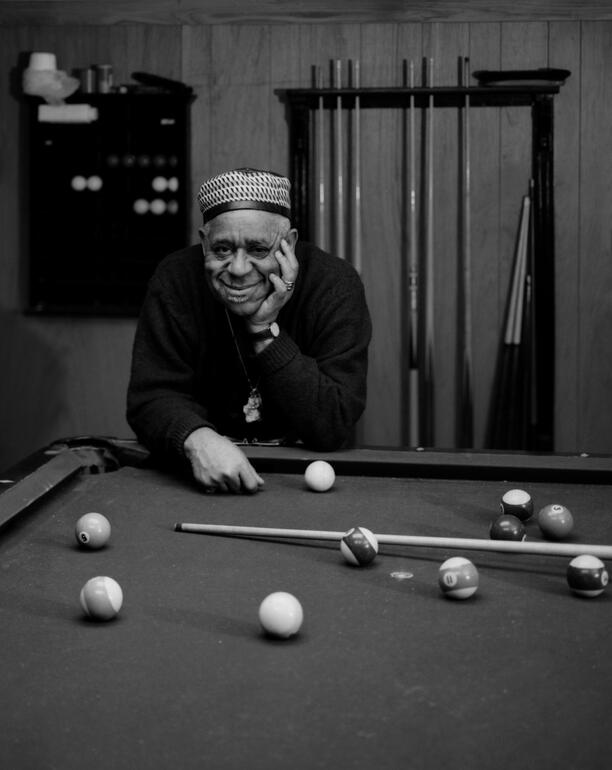

Dizzy Gillespie at Home, Englewood, New Jersey, March 19, 1991

What makes O’Neal unique is how unassuming and disarming he is. He’s hobnobbed with the stars, is often a guest speaker and an honored guest dressed in a tux, but always rides the subway to get to a banquet at “the Met” or an uptown soiree. At the same time, he is always happy to share a lunch at the hamburger place around the corner and relate his latest adventure. But under the smooth Texan charm is an adroit producer, a discerning jazz connoisseur and a perceptive photographer, capturing the sense of time and place in American culture.

The Great Migration of Black Americans moving north gave birth to the Harlem Renaissance and the popularization of jazz in America. Some of the first coast-to-coast radio broadcasts were live from Harlem ballrooms such as the Savoy and the Cotton Club, featuring the likes of Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway. O’Neal knew and recorded many of the musicians who had performed during the heyday of the Harlem jazz scene. For 10 years, he worked on his book, The Ghosts of Harlem, finally publishing it in 1996 in France and in 2006 in the U.S. O’Neal interviewed and photographed more than forty jazz legends, often in their homes and neighborhoods. Greats such as Dizzy Gillespie, Joe Turner, Maxine Sullivan, Danny Barker, Doc Cheatham and Zoot Sims are just a few of the hundreds of musicians he has known, photographed and recorded.

The image of Zoot Sims was made in 1974 at Downtown Sound, O’Neal’s recording studio. Sims was a saxophone giant who played with Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Buddy Rich, along with countless others, and played background on several of Jack Kerouac’s spoken-word recordings.

The Great Migration of Black Americans moving north gave birth to the Harlem Renaissance and the popularization of jazz in America. Some of the first coast-to-coast radio broadcasts were live from Harlem ballrooms such as the Savoy and the Cotton Club, featuring the likes of Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway. O’Neal knew and recorded many of the musicians who had performed during the heyday of the Harlem jazz scene. For 10 years, he worked on his book, The Ghosts of Harlem, finally publishing it in 1996 in France and in 2006 in the U.S. O’Neal interviewed and photographed more than forty jazz legends, often in their homes and neighborhoods. Greats such as Dizzy Gillespie, Joe Turner, Maxine Sullivan, Danny Barker, Doc Cheatham and Zoot Sims are just a few of the hundreds of musicians he has known, photographed and recorded.

The image of Zoot Sims was made in 1974 at Downtown Sound, O’Neal’s recording studio. Sims was a saxophone giant who played with Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Buddy Rich, along with countless others, and played background on several of Jack Kerouac’s spoken-word recordings.

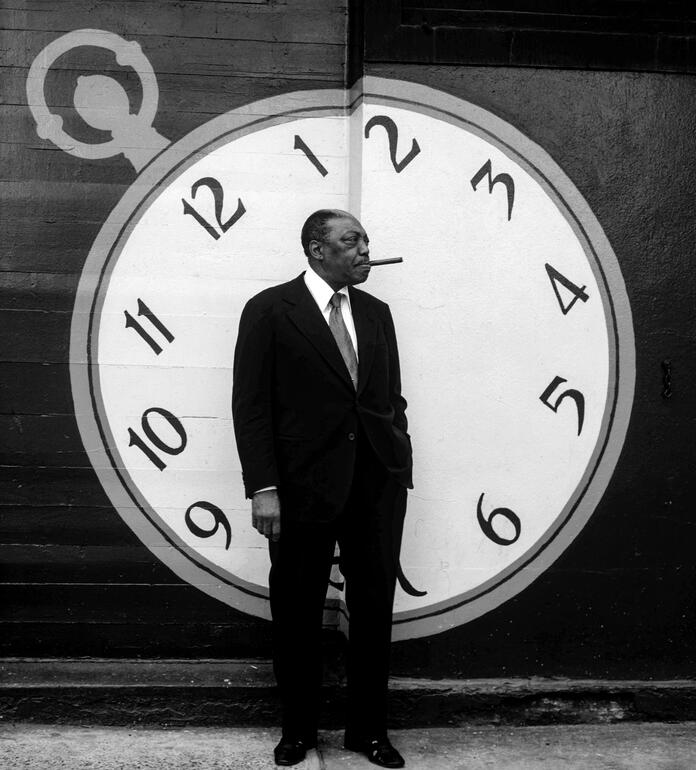

Joe Turner, New York City, August 25, 1978

O’Neal was used to seeing the singer Maxine Sullivan dressed to the nines when she performed, but when he visited her home in the Bronx in the year before her death, she was dressed in a cotton jumpsuit and bedroom slippers. Posing for O’Neal on her front stoop, she told him, “What you see is what you get.”

O’Neal photographed Doc Cheatham in his kitchen on Lexington and 101st street. Cheatham was the lead trumpet for Cab Calloway in the 1920s and 1930s, moving over to Latin bands after WW2. He returned to jazz when he was in his 60s and played well into his 80s. He made his last record in 1998 just before his death, for which he won a posthumous Grammy. In 1977, testing a studio microphone, Doc sang “What Can I Say Dear After I Say I’m Sorry.” The recording became so popular that he continued to sing lead vocals. “He was a wonderful guy and played every Sunday at Sweet Basils, and often walked from his home on 101st street, where I took this image, to the Village and beyond.”

In 1987, Hank went to New Orleans to scope out young jazz bands for the Floating Jazz Festival that he and his wife Shelley Shier organized for Norwegian Cruise Lines and Cunard between1983–2002. It was in New Orleans that he photographed Danny Barker, who had played in Harlem with Benny Carter and Cab Calloway. Barker mentored many of the younger jazz greats, such as Wynton Marsalis, and is credited with saving New Orleans jazz for a generation. O’Neal remembered him as, “a real sweetheart, who always gave back to the jazz community.”

O’Neal photographed Doc Cheatham in his kitchen on Lexington and 101st street. Cheatham was the lead trumpet for Cab Calloway in the 1920s and 1930s, moving over to Latin bands after WW2. He returned to jazz when he was in his 60s and played well into his 80s. He made his last record in 1998 just before his death, for which he won a posthumous Grammy. In 1977, testing a studio microphone, Doc sang “What Can I Say Dear After I Say I’m Sorry.” The recording became so popular that he continued to sing lead vocals. “He was a wonderful guy and played every Sunday at Sweet Basils, and often walked from his home on 101st street, where I took this image, to the Village and beyond.”

In 1987, Hank went to New Orleans to scope out young jazz bands for the Floating Jazz Festival that he and his wife Shelley Shier organized for Norwegian Cruise Lines and Cunard between1983–2002. It was in New Orleans that he photographed Danny Barker, who had played in Harlem with Benny Carter and Cab Calloway. Barker mentored many of the younger jazz greats, such as Wynton Marsalis, and is credited with saving New Orleans jazz for a generation. O’Neal remembered him as, “a real sweetheart, who always gave back to the jazz community.”

One of the great stride piano players was Joe Turner, who O’Neal recorded in 1978 for Chiaroscuro Records. The title of the album was As Time Goes By, so for the cover, O’Neal took Turner up to a clock shop on 53rd Street, where he made a dozen or so images of Turner in front of the clock faces. Turner had moved to Paris after WW2 to escape the pain and prejudice of being Black in America. In Paris, he performed regularly until his death in 1990.

Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who helped usher in the Bebop era with Charlie Parker, was an avid photographer himself, and on occasion O’Neal would help Dizzy fix his cameras. Gillespie lived in Englewood, New Jersey. The finished basement of the house was his domain, where he had an office and a pool table. O’Neal made the photograph of Gillespie at the pool table on one of his many visits. Gillespie was later diagnosed with cancer. After being treated, he extracted a promise from his oncologist to never turn away a jazz musician in need. This led to a pro-bono network of doctors that served and saved many musicians through the work of the Jazz Foundation of America, on whose board O’Neal still sits.

Besides his jazz portraits, O’Neal’s pulse on the contemporary art movement of New York City is captured in his forty-plus years documenting street art. Many of his images remain the only record of this important art movement, including the earliest works by Keith Haring and recent works by Banksy. O’Neal’s book XCIA’s Street Art Project, published in 2011, is a who’s who of New York street art, from the defaced 1978 “Cancer Eyes” cigarette billboard to now lost and lamented 5Pointz mural space in Long Island City.

Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who helped usher in the Bebop era with Charlie Parker, was an avid photographer himself, and on occasion O’Neal would help Dizzy fix his cameras. Gillespie lived in Englewood, New Jersey. The finished basement of the house was his domain, where he had an office and a pool table. O’Neal made the photograph of Gillespie at the pool table on one of his many visits. Gillespie was later diagnosed with cancer. After being treated, he extracted a promise from his oncologist to never turn away a jazz musician in need. This led to a pro-bono network of doctors that served and saved many musicians through the work of the Jazz Foundation of America, on whose board O’Neal still sits.

Besides his jazz portraits, O’Neal’s pulse on the contemporary art movement of New York City is captured in his forty-plus years documenting street art. Many of his images remain the only record of this important art movement, including the earliest works by Keith Haring and recent works by Banksy. O’Neal’s book XCIA’s Street Art Project, published in 2011, is a who’s who of New York street art, from the defaced 1978 “Cancer Eyes” cigarette billboard to now lost and lamented 5Pointz mural space in Long Island City.

O’Neal also photographed Richard Hambleton’s “Shadow Man” as it appeared surreptitiously all over the city in the 1980s, as well as Shepard Fairey’s color-saturated manifestos. The book remains a vital art historical research source, and includes an invaluable thumbnail index for future generations of art and cultural historians.

O’Neal admits to feeling his age at 82, but he doesn’t act his age. He is still running from one appointment to the next, meeting for lunch while planning the next book and another project. And, fortunately for us, photographing every step of the way.

Addendum

All images copyright Hank O’Neal. You can see much more of his work at hankoneal.com.

O’Neal admits to feeling his age at 82, but he doesn’t act his age. He is still running from one appointment to the next, meeting for lunch while planning the next book and another project. And, fortunately for us, photographing every step of the way.

Addendum

All images copyright Hank O’Neal. You can see much more of his work at hankoneal.com.